ARTISTS IN N. 85

Vic Bakin

Fiorella Baldisserri

Bob Miller

Andrea Sawyerr

Gabriele Cecconi

Angelo Del Negro

Antonio Tudisco

Simone Tramonte

Alexandra Cool

Frédérique Gélinas

Yves Lacroix

Natale De Fino

Mauro Splendore - Sonia Navelli

New Releases

Massimo Magistrini: IN - Collana CAPSULE PHOTO di Gente di Fotografia

It is

around grammar that Massimo Magistrini's work revolves, like the needle of a

compass.

The very title of the book is entrusted to a preposition, In,

which later becomes a prefix to introduce the internal sections. With a daring

move, a simple particle takes on the task of deciphering a complex work,

articulated in several series that, when considered as a whole, provide a

precise vision of photography and the natural world.

Behind the camera, the author adopts the attentive gaze of the hiker who moves

through minimal environments but knows how to imagine boundless realities,

scrutinizing and consulting woods, herbs, wildflowers, moss, and ancient

nautical maps. [...]

In-canto

(TN: en-chantment) is the chapter that opens the book and transports us

into the woodland dimension, into an archetypal place where exuberance and

mystery dwell. It is the double exposure in-camera - not in post-production -

that gathers them both, giving life to a process of sedimentation and

transformation that alludes to the physiological and symbolic implications of

forest regeneration.

In-colto

(TN: un-tended),

which follows, instead interprets the idea of a garden, a well-protected hortus

conclusus, well guarded by the edges of the image and populated by

common yet extraordinary specimens. Here, in addition to the double exposure

that emphasizes various combinations of elementary botanical forms, it is the

black and white that synthesizes the entire sequence, converting it into a

gallery of sophisticated tapestries.

In-esplorato

(TN: un-explored),

lastly, contains two fantastic maps created with images of mosses and conifer

leaves, to which a third map is added, built with details extrapolated from an

ancient portolan chart. [...]

(Laura Manione)

iara di stefano: di Miele e di Fiele - Collana CAPSULE PHOTO di Gente di Fotografia

Honey and Gall—two substances with opposing sensory profiles, often entwined in symbolic contrast. “Mel in ore [...] fel in corde” (honey in the mouth, gall in the heart), reads a medieval Latin proverb; “in corpo fiele, in bocca miele” (gall in the body, honey on the lips), wrote Pirandello in The Man, the Beast and the Virtue.

With this title, Iara Di Stefano invokes an ancient dualism to frame the narrative of a pivotal year - a turning point in her own life. The book unfolds through contrasting materials and shifting registers, creating a rhythm of fracture and recomposition. Yet from these apparent disruptions, a kind of organic unity emerges - almost biological in nature. The photographs act as surfaces upon which both sweetness and bitterness accumulate, like traces left behind by experience.

(from the presentation text by Laura Manione)

Silvio Canini: UMBRATILE - Collana CAPSULE PHOTO di Gente di Fotografia

It was common in the 1960s, and perhaps even earlier, to rent out one’s home to vacationers who came to spend their holidays by the sea, in order to earn some extra money. Meanwhile, we would sleep in the garage, where we had managed to set up a bathroom.

The less fortunate made do in the shed.

Tourists would stay for the entire season, bringing the whole family along, including grandparents. Only the father sometimes had to return home to work — unlike today, when even managing a weekend away feels difficult.

My parents owned a haberdashery on the main avenue and didn’t have much time to look after me, so during the summer, I became the child of the tourists and a sibling to their children. I often ate with them and spent the whole day at the beach, making the most of the sun until it disappeared.

I remember that towards the end of the day, we would search for the last rays of sunlight to finish our sandcastles, as those giant concrete buildings cast long shadows.

(Silvio Canini)

Alessandro Mallamaci: Un luogo bello • SECOND REPRINT

A project that has received many awards:

- Winner of the InTarget Award and selected for an exhibition at the Photolux Festival, Lucca, Italy, 2024.

- Selected for the Lishui Photography Festival, Lishui, China, 2023.

- Winner of the Open Call and selected for The performing photobook exhibition, curated by Francesca Serravalle at the Format International Photography Festival, Derby, UK, 2023.

- Winner of the Open Call, juried by Paul D’Amato, and selected for the Back on the Shelf book exhibition, at Filter Photo, Chicago, USA, 2023.

- Winner of the International Open Submission and selected for the Photobook exhibition at the Belfast Photo Festival, Belfast, UK, 2022.

The title is: “A beautiful place”

To get to the heart of his story, Alessandro Mallamaci gives us two points of reference. The first is geographic: “The valley of the Sant’Agata river nestles in the red land of the Aspromonte mountains in the province of Reggio Calabria and flows towards the sea until it plunges into the Strait of Messina. The name of the waterway originates from the Greek aghatè, which is linked to concepts such as beauty, goodness and nobility; as if travellers from the Magna Graecia period had been enchanted by this place.” The second is sentimental, a kind of afterword to clarify the title of his work: “This is my landscape. I cannot help but love it. It is a beautiful place.” An unasked-for explanation which highlights, from the very first image, his deep bond, but also a conscious and painful one, for a beloved landscape.

Now the journey can begin. We are in Calabria, in the places where Mallamaci lives. Places which contrast sublime landscapes and building speculation, uncontaminated nature and nature corrupted by man and his stories, historic remains and industrial waste, popular traditions rich in charm and the rule of the ‘Ndrangheta. Contradictions, as he himself points out, are the leitmotiv of this area of Italy, and Mallamaci has been moving and working between these alternations for five years. He seeks the proper distance for his photography, one which allows a dialogue between details and wider visions, people and things, to build an itinerary which develops upwards and into which – almost a pause – horizontal visions are inserted.

(from the text by Giovanna Calvenzi)

Paolo Ferrari: LA NATURA DELLE COSE

There is an order in things, a right measure, a balance.

And if not, if chaos, dissarray were to regulate nature, society, up to the humanized landscape, then Paolo Ferrari’s gaze intervenes to find the matter in disorganized objectivity, the primordial substance for the creation of one’s own ordered world, one’s own cosmos. Just as ancient philosophers drew from sensorial data to discuss the world of the invisible, so in the author’s shots the collected reality comes to life and takes shape, transforming itself into a metaphor of animated, indeed humanized, everyday life, open to the gaze. Contemplation is therefore the starting point and the arrival point; the absence of excess determines a classic vision of elegance, serenity and balance. Consistently with this assumption, the attraction that the ordered cosmos exercises on man, by virtue of the beauty it expresses, has always been linked to the idea of eidos form, which coincides with the “thing seen”. And why not translate the concept into the “thing photographed”? The gaze sees, chooses, collects, stops time and creates space.

(from the text by Stefania Lasagni)

The shattering charm of a swing, a leap into the void, that vertigo like an inebriation which – averting me from the real world and the rational sphere – takes me to that suspended Middle Earth, to the edge of an imponderable abyss in whose darkness the whirlpool of life appears to me. It’s impossible to escape this game capable of awakening a sense of wonder, in a sort of monologue between me and myself, which investigates the many facets of the nature of things. Through shadows and reflections I realize that by removing myself from the things that surround me, I give them back their original dignity and, with it, also an autonomy from my attention, from my energy, which frees them and allows them to soar. The world becomes a mirror of my most hidden contents and my projections, in a completely unconscious and involuntary way. Windows as observation and dialogue points. Flights of flocks that arouse my imagination. Contexts aimed at making me listen to the extraordinary symphony of existence.

Paolo Ferrari’s book is written with photography as communication based on the transmission of authentic messages, faithful to the author’s being and impossible to enclose in the mere convention of speech.

(from the text by Daniela Bazzani)

Giorgio Dellacasa: LA HABANA - FOTOGRAFIE DA UNA CITTÀ CHE RICAMBIA LO SGUARDO

Las imágenes de Giorgio Dellacasa, pertenecientes a la segunda generación de fotógrafos occidentales que arribó a la isla entre finales del siglo pasado y nuestros días –entre los que se encuentran Martin Parr y, sobre todo, Alex Webb– se inscriben plenamente en la denominada fotografía callejera, o eso podría parecer. Sin embargo, el condicional es obligado, ya que es preciso incluir ese instinto de viajero auténtico que mueve al ser humano a la comprensión y la inclusión, al tiempo que rehúye toda forma de depredación, incluida la depredación visual de la que a menudo está impregnada la fotografía callejera.

Así, en los breves textos autógrafos que acompañan el libro y lo transforman idealmente en una especie de cuaderno ilustrado y nos permiten adentrarnos en los entornos neurálgicos y periféricos de la capital de una manera no invasiva.Empezando por el título, en el que se habla de intercambio de miradas– se trata realmente de una conversación y no de un monólogo, con todos los matices que, aplicados a la gramática fotográfica, sugieren una conversación amistosa.

Las luces suaves o filtradas pulen los tonos e invitan a la intimidad; las amplias y nítidas zonas de sombra marcan quizá un silencio impenetrable, estableciendo un límite a nuestra presunción; la proximidad o distancia con los individuos, así como sus gestos, miden el espacio de interlocución y admiten distintos grados de confianza. Además, al estar presentes en varias imágenes, los encuadres semisubjetivos o «naturales», como los definía Luigi Ghirri, además de guiar la mirada, nuevamente actúan como elementos discursivos, ya que introducen breves pero agudos comentarios al diálogo.

En definitiva, Giorgio Dellacasa no habla de La Habana, habla con La Habana.

(desde la introducción de Laura Manione)

Mario Cucchi: C'est la vie...

Photographs of well-composed objects, but with something odd, which makes them like surreal and extravagant toys. However, without any dramatic tension, without any disturbing atmosphere. Even the black and white seems subtle. And the composition is balanced, perfect, as only a master of still life, which Mario Cucchi undoubtedly is, can do. Even the title, C’est la vie, has something merry, but with a bitter hint.

(from the

introduction by Gigliola Foschi)

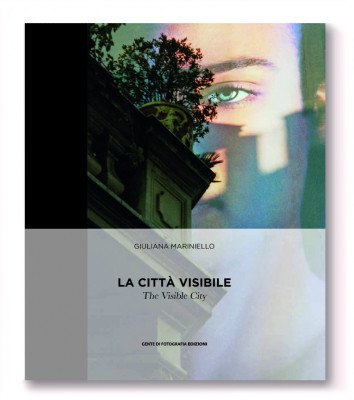

Giuliana Mariniello: LA CITTÀ VISIBILE (The Visible City)

The city that Giuliana Mariniello chooses to depict, in fact, is the one that the eyes perceive: characterized by scaffolding covered with tarpaulins decorated with advertising images or by reproductions of the hidden architectural structure; it is the space punctuated by billboards placed against the background of the buildings; it is public vehicles disguised with decals. Her photographic transcription of this environment, which we almost always perceive unconsciously and without committing ourselves to look in order to understand, is reinterpreted through a selective framing and with the judicious use of the Matisse tradition of à plat, so as to radically transform the proxemic relationships between the things represented and to arouse new meanings, frequently full of irony.

(from the introduction by Massimo Mussini)

LAST ISSUE

SUBSCRIBE TO GENTE DI FOTOGRAFIA

Six-monthly magazine.

172 pages, format mm 220 x 300.

The publication is aimed at an audience of professionals photographers, artists, gallery owners, amateurs and operators of cultural sector as a source for further study, debate and anticipation of creative trends.

TABLE OF CONTENTS 85

Editoriale

LONTANANZA

di FRANCO CARLISI

Portfolio

Andrea Sawyerr

IL DESERTO CHE AVANZA

di ENRICO MONCADO

Gabriele Cecconi

DA UN ALTRO MONDO

di ALBERTO GIOVANNI BIUSO

Simone Tramonte

NET-ZERO TRANSITION

di GIUSY RANDAZZO

Angelo Del Negro

IL TEMPO DELL’ATTESA

di OSCAR MEO

Yves Lacroix

WHEN OUR PATHS CROSS

di ATTILIO LAURIA

Vic Bakin

EPITOME

di MARCELLA BURDERI

Frédérique Gélinas

EL TIEMPO DEL MAGUEY

di TEODORA MALAVENDA

Bob Miller

I FIGLI DELLA TERRA

di MARCOSEBASTIANO PATANĖ

Alexandra Cool

LA PREISTORIA DEL NULLA:

THE TIME BEING

di ENRICO PALMA

Antonio Tudisco

LA VISIONE CHE RISCRIVE

IL REALE

di MONICA MAZZOLINI

Natale De Fino

POLAROID

di SIMONA LORENZANO

Fiorella Baldisserri

IL CINEMA DEL DESERTO

di SERGIO LABATE

Mauro Splendore

Sonia Navelli

L’ARMONIA PRESTABILITA

di SARAH DIERNA

Close Up

FRANCO CARLISI INTERVISTA

MARIATERESA CERRETELLI

Mostre

Mohamed Bourouissa

di LOREDANA CAVALIERI

Mario Giacomelli

di ALBERTO GIOVANNI BIUSO

Isole minori

di GAIA CARLISI

Libri

Massimo Magistrini

IN

di LAURA MANIONE

Iara Di Stefano

DI MIELE E DI FIELE

di LAURA MANIONE

Alessandro Mazzola

H.M.

di DARIA BAGLIERI

Pierfrancesco Celada

WHEN I FEEL DOWN I TAKE A

TRAIN FOR THE HAPPY VALLEY

di PATRIZIA SOMMELLA

Ulderico Tramacere

LORO

di PIPPO PAPPALARDO

Festival

Cortona on the Move

COME TOGETHER

Festival della Fotografia Italiana

IL POTERE

DELL’IMMAGINAZIONE

di Martina Morreale

Yeast Fotofestival

(N)EVER ENOUGH

Premio

Kamira Photo Award 2025